Several dolls are attributed to early American doll maker, Leo Moss. Hand crafted during the period referred to as the Emergence of Modern America, from 1890-1930, and at least two years beyond, some Moss dolls purportedly migrated to Europe. It was not until the early 1970s, several years after his demise, however, that Moss, described as a Macon, Georgia handyman by trade, gained recognition for his dolls. In Black Dolls an Identification and Value Guide 1820 to 1991 (BD book 1), author, and well-known black-doll historian, Myla Perkins, attributes discovery of Leo Moss dolls to one of her personal friends, Betty Formaz. A collector herself, Formaz also restored and made dolls. Although the manner by which Formaz became acquainted with Moss’s Georgia descendants remains a mystery, her unearthing created an eventual desire in many collectors to own Moss dolls.

Moss dolls fall into several categories. These include early American character dolls, papier-mâché, folk, and one-of-a-kind artist. The dolls have papier-mâché character heads. Other common characteristics include bodies which are usually cloth, natural-textured hair, and inset glass eyes. Mohair or human hair was used for some dolls. Sizes vary with dolls said to have been created in the likeness of family and friends and other people Leo Moss knew. Moss dolls typically depict infants, toddlers, young children, and adults. Smiling, stoic, and even sad expressions are found on the faces of Moss dolls. A recognizable feature of many of his child dolls is the occasional signature teardrop or two on their cheeks. Moss dolls can be either unmarked or marked “L.M.” An inscription of the person’s name after whom the doll was sculpted and the year made is usually located on the cloth body. Other Moss dolls have their names incised into the shoulder plate.

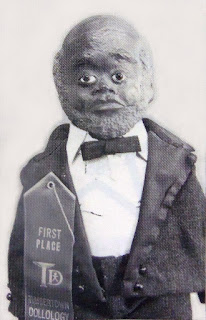

|

| Leo Moss self-portrait doll |

In the February/March 1985 issue of Doll Reader magazine, an invaluable doll described as a self-portrait of Leo Moss is featured in an advertisement on page 29. The ad was placed by The Country Bumpkin Doll Shop announcing their March 30, 1985, auction held at the Sheraton of Boca Raton, Florida. The black and white ad image illustrates a mature male doll with balding papier-mâché head, inset eyes, closed mouth with down-turned full lips, and full molded beard. The doll is dressed in a tuxedo with a first place ribbon from Timbertown Dollology attached to the coat. The magazine photo caption reads: “Very Rare – All Original ‘Mr. Leo Moss.’” This photograph, courtesy of Dolls magazine (which merged with Doll Reader in January 2012) may be the doll community’s only image of this extraordinarily talented doll maker. The same doll, in a color photograph from Pinterest.com pinned from the Theriault website, is the featured doll of this article.

Well known for his black dolls, white Moss dolls have also been documented. This is confirmed in the article, “After 10 Years Antique Doll Collection Numbers 250,” written by Reginald Stewart, published in The Dispatch, January 10, 1978. Stewart’s article explores Myla Perkins’ antique doll collection. In this article, Perkins shared, “Moss, it has been found, made white dolls in the image of white children in the Macon area in exchange for the materials he needed for making black dolls… His work was quite detailed and hair used on the white dolls was natural hair. His wife would make the clothes for the dolls.” Further documenting the existence of white Moss dolls, on page 13 of BD book 1, Perkins illustrates and describes Elaine, an 18-inch (46 cm) Caucasian doll. According to Perkins, “Elaine was sold in 1972 by the sister of the girl the doll was made for.” A letter written by the doll’s seller to the 1972 buyer quite eloquently describes her family’s affection for the gentle giant, Mr. Leo Moss, and his wife, Lee Ann. The Moss couple had worked for the seller’s parents during her childhood. In the letter, the seller describes the delight she and her two sisters experienced upon receipt of dolls for Christmas, 1909, made in their likeness by Mr. Moss. According to the letter, Moss’s wife made the dolls’ clothing that matched dresses she made for the girls.

In Mr. Stewart’s article, Perkins describes Moss’s papier-mâché process, as the use of “scrap wallpaper… picked up from his odd jobs,” such as those he performed when working for the above-mentioned family in 1909. Perkins continues, [Moss used] “soot from stoves and chimneys… for coloring the skin.” While papier-mâché was used to fashion the dolls’ heads and shoulder plates, many of the bodies were reportedly purchased from a New York toy dealer, who allegedly caused eventual woe for Mr. Moss.

In BD book 1, Perkins described Moss’s life as very tragic. His wife ran off with the toy dealer from whom he often purchased supplies, taking only the youngest of their five children with her. Moss was left alone to raise their remaining four children. As an expression of his sadness, legend has it that Moss began adding the signature tears to some of his dolls after his wife’s desertion. However, Perkins attributes the tears to those shed by a child when Moss sculpted its portrait. “According to his daughter, Ruby,” Perkins writes, “when he was making the doll face of one of the toddlers in the family, the child became impatient while sitting and began to cry… Moss tried to get the child to stop crying without success. Finally he said, ‘if that’s how you want to look, that’s how I’ll make your doll.’ … Afterwards, whenever a child cried when Mr. Moss was making a portrait doll, the doll then also had tears.”

(Continue reading here.)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for reading and for sharing your thoughts. Please feel free to share the link to this blog or post with those who will enjoy reading it.